I recently learned two Swedish words – flygskam and tågskryt. These translate to “flight shame” and “train bragging,” labels that reflect a sentiment among a growing number of people in Northern Europe to reduce their carbon footprints by replacing short-distance air travel with land travel, namely rail.

The topic is getting more publicity as the effects of climate change become more pronounced and people and industry realize they must make changes to slow the alarming rate of global warming. I’m concerned with the planet’s future. I want my children to live on a planet that’s as healthy as possible. However, it’s disconcerting to see air travellers are targeted, or shamed as the Swedish words imply, for choosing to fly.

It’s more of a shame that people don’t know just how far our industry has come in reducing the carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide emissions of commercial aircraft. The reductions are significant, and may even surprise you. Our sustainability plan to tackle the impact of climate change is among the most ambitious and globally-focused of any industry. Many sectors of the global economy would be envious of our track record. Perhaps we just haven’t done a very effective job of publicizing our accomplishments.

By the way, flygskam was a topic at the IATA Annual General Meeting in Seoul last June. Notwithstanding the distance associated with my 11-hour nonstop, I wasn’t ashamed to fly to Korea. The carbon dioxide emissions of my flight from London to Seoul were about 65% lower than that same flight in 2004, thanks largely to more fuel-efficient aircraft. It is an impressive improvement.

But how do we tell the world that we’re making tremendous progress reducing our industry’s emissions?

Here’s my contribution.

Aviation’s Footprint

Aviation represents US$2.7 trillion (3.6%) of the world’s GDP. Every day, 100,000 flights carry 12 million passengers and US$20 billion worth of world trade. Just 15 years from now, passenger volume is expected to double to a staggering 25 million per day. That’s equivalent to the population of Australia.

According to the Air Transport Action Group (ATAG), emissions from aviation are less than the iron and steel industry (5%), cement production (4%) and the shipping sector (3%), and around the same as the servers and transmission cables of the internet. Aviation represents 2% of all human-generated CO2 emissions.

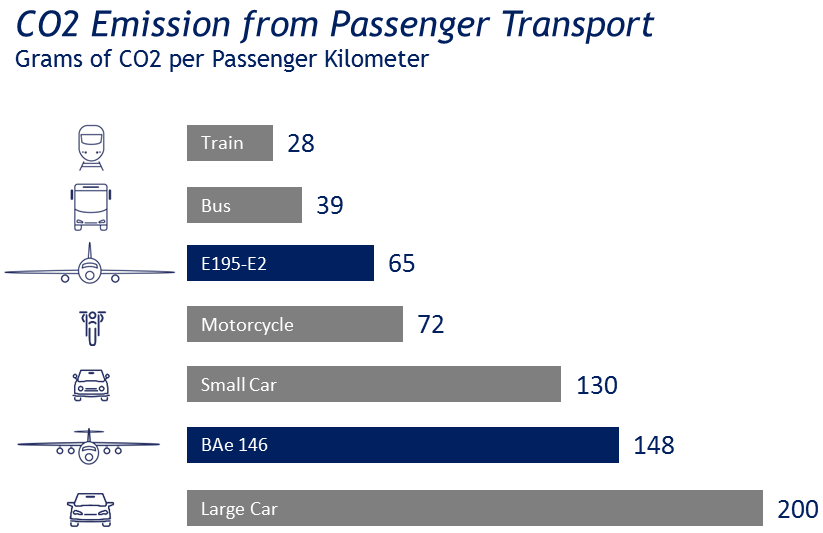

Now here’s where it gets interesting. When you consider all modes of transportation, commercial aviation accounts for 12% of emissions. Road vehicles, by comparison, are responsible for 74%. Of course, there are more automobiles and trucks than airplanes, but today’s new-generation aircraft, like our E2s, are incredibly efficient. The E2s use fewer than 3 liters of fuel per 100 passenger-kilometers – that’s much more efficient than a compact car. Aircraft today are well over 50% more fuel efficient per passenger-kilometer than the commercial jets of the 1980s.

So, even as the number of travelers is going up, we’re moving in the right direction by bringing fuel consumption and emissions down. Until aircraft are all electric powered, it’s still a comparatively clean way to travel.

Train or Plane? Which is the Better Choice?

Advocates of tågskryt, extolling the benefits of train travel, may not be accounting for the carbon footprint of railway infrastructure. In addition to the CO2 emissions from normal rail operations, infrastructure adds as much as 80% to rail’s overall carbon footprint. Nonetheless, train travel is a low-emission, logical option for short-distance travel. Some 80% of train passengers take trips that are 300 km, or less. The majority of airline passengers fly longer distances – 75% in the USA, 80% in Europe, and 85% in Japan.

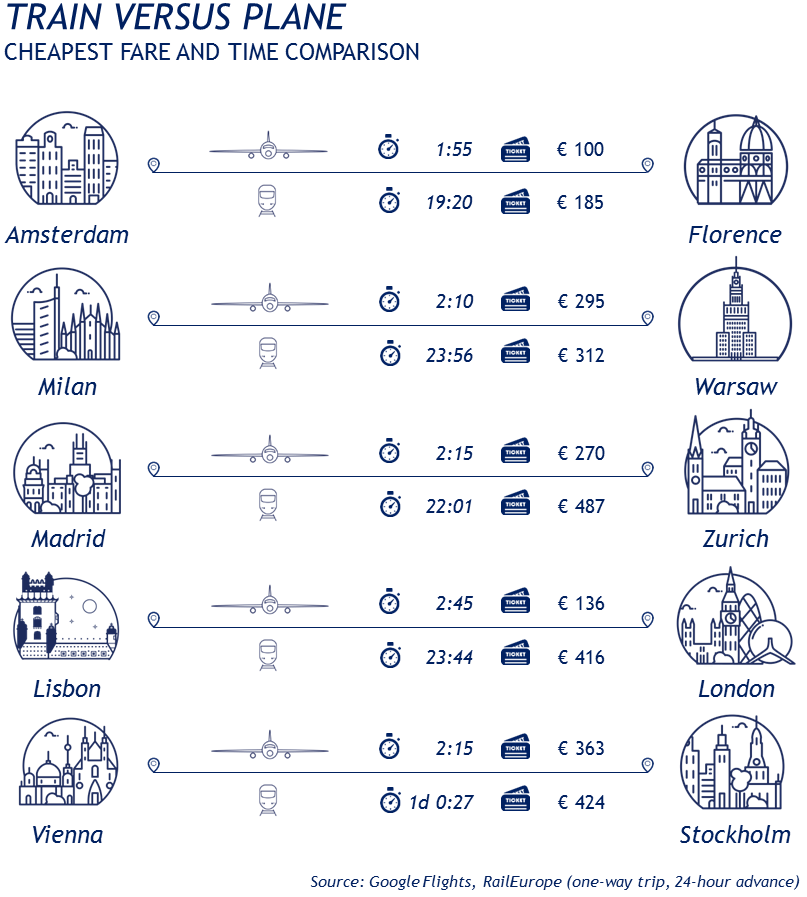

So, should we all take the short-haul train to the long-haul plane? KLM CEO Pieter Elbers has said that if Europe was to offer more efficient high-speed rail systems, he would support intermodal alternatives. It’s a great idea, but it’s not always practical when you factor time and cost into the options of going from A to B via C. KLM made a step with its Fly Responsibly initiative with a call for action and collaboration to reduce CO2 around flying.

Getting to the airport is almost always more time consuming than getting to a train station where you need to arrive only a few minutes before departure. For a short-haul trip of one hour in the air, travel time to/from the airport, security, and baggage claim may add three hours to the journey. It’s extra time yet train travel is often more expensive, by a wide margin.

Even with fewer carbon emissions by rail, it’s not easy to convince people to swap a cheaper, faster flight for a much longer, more expensive train ride. The more efficient mode for mid to long-distance transport is always air, especially when you consider all the economic and productivity factors. By all means, take those high-speed trains on high-density corridors like Beijing-Shanghai, Washington-New York, and Madrid-Barcelona. But regional airplanes will continue to be the backbone of traditional hub and spoke systems when there is not enough demand to warrant frequent train service between, say, Tacheng and Urumqi, Linköping and Amsterdam, or Abilene and Dallas. One-stop air service to a hub brings you to the world, quickly, efficiently, and cheaply.

Making Tremendous Progress

We’re already pursing the short, medium, and long-term goals set by ATAG.

In the short-term, the results are better than expected. The goal to improve average annual fuel efficiency from 2009 to 2020 by 1.5% is, to date, coming in at 2.3% because airlines are flying more efficient aircraft. The technology on new-generation airplanes is helping them reduce fuel burn between 15% and 20% compared to older fleets.

What’s really impressive is what has happened in the USA, the world’s biggest air travel market. Annual emissions from U.S airlines dropped 3% over the last 15 years even though traffic rose 24%. That dramatic reversal in emissions is largely due to the airlines’ acquisition of new aircraft.

The medium-term goal is ambitious: to stabilize net aviation CO2 emissions worldwide at 2020 levels. It’s a bold target that requires the industry to commit to ICAO’s CORSIA agreement in which CO2 emissions from aviation are offset with reduced emissions elsewhere. In other words, any emission that the aviation industry is unable to reduce through technological, operational or infrastructure means, or by using sustainable aviation fuels, will need to be offset by market-based measures.

But that’s not all. Beyond carbon offsetting, the industry is pursuing initiatives to reduce unnecessary aircraft weight, adopt more performance-based navigation systems to cut flight time, introduce electric taxiing to decrease engine hours, and develop biofuels. You may remember that Embraer was a pioneer in the field. Sustainable aviation fuel is particularly effective since it can reduce CO2 emissions as much as 80% compared to traditional fuel.

Charging Ahead to the Future

Finally, there’s the big, audacious goal: to halve net CO2 emissions by 2050 compared to 2005. Aircraft and engine manufacturers will lead the charge, literally. This won’t be an evolution. Instead, the target calls for a complete revolution in design and technology. And we’re already taking baby steps in that direction.

As battery technology develops, increased energy storage may make electrically-powered commercial flight a reality. There are already several small-scale examples out there. One really exciting project is Embraer’s prototype for an electric Ipanema agricultural aircraft. It’s already under development in partnership with engine manufacturer WEG and is a true stepping-stone for further advancements.

Over the next few years, electric propulsion is likely to be limited to aircraft for air taxis, island hopping, flight schools, skydiving and crop-dusting. Longer term, we’ll be able to add range and payload, reduce battery weight, and increase the energy density of stored electricity. It’s only a matter of time before we see electric propulsion on commercial aircraft, starting in the regional space.

There’s also a lot of research with hybrid and even fully-electric options that combine the performance of sustainable liquid fuel with the efficiency of electric power. This will be an option for mid to long-range flights in the future. I’m encouraged that airlines, airports, ATC providers, aircraft, component and engine OEMs – all the industry players – are embracing initiatives to reduce the size of aviation’s carbon footprint.

The impact of climate change has no borders. Carbon emissions affect everyone. I’m confident our industry will rise to the challenge to be even greener. We’ve already made dramatic improvements, but my colleagues and I recognize that it’s simply not enough. We must do more, and we will.

I truly believe the best is yet to come.