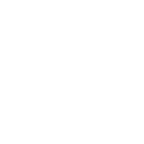

One of the most important short-term drivers shaping the airline industry has been the large fall in the price of oil. Capacity decisions, including aircraft retirement, route planning, and pricing were all influenced by the input cost of fuel. The lower price of oil tempts airlines into backsliding on their strategy of disciplined growth, as it reduces the pressure to cut costs and capacity.

The rapid reduction in the barrel price from USD 100 to USD 30 made a massive difference to the shape of the industry; particularly in an industry which typically records such low profit margins.

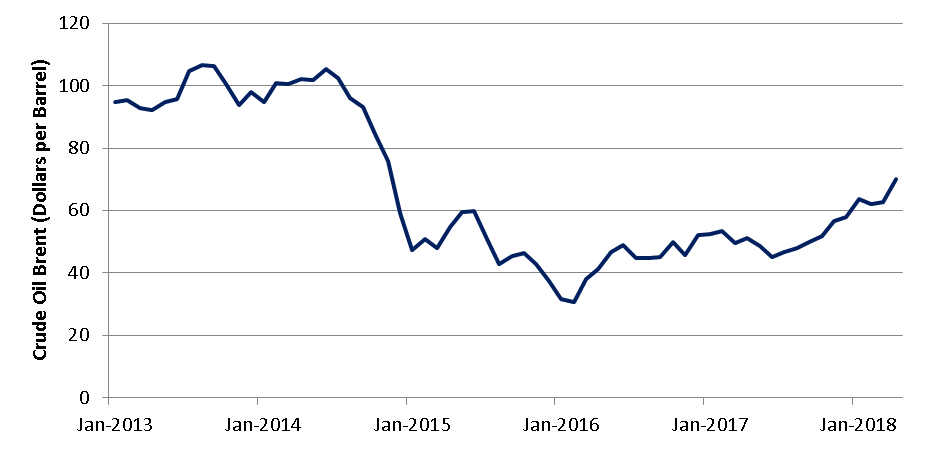

Beyond the obvious near-term positive impact on balance sheets and cash flows, there is the ever-increasing threat of overcapacity. The glut of available seats has impacted ticket prices, leading to significant fare discounting. The market became even more strongly stimulated by supply driven growth, in the form of lower air fares that may not be sustainable over the long run.

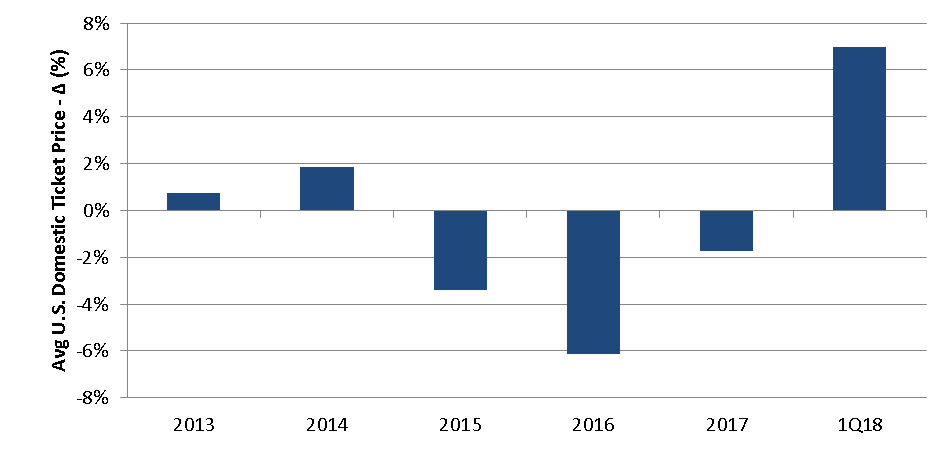

The current economic performance of the airline industry is no guarantee of future results. Performance, by definition, is a snapshot of the past. Profits may now erode and gains may be wiped out with rising oil prices, bringing the profitability stake back to the rare and the few. The price of oil has just hit USD 70 a barrel, the first time since December 2014, and that must encourage discipline.

Delta Air Lines saw its operating profit slide 16% during the first quarter of 2018, largely due to a run up in oil prices. A steeper increase in operating expenses overshadowed the Atlanta-based carrier’s record operating revenues during the period, a trend that its peers will soon follow suit during their 1Q18 earnings over the course of the next days.

Total unit revenue is coming in the high end of guidance for US airlines, mainly driven by higher fares. After falling steadily since 2015, average U.S. domestic ticket price is up 7% in the first quarter of 2018.

The ability to shift back towards sustainable revenue unit growth, instead of aggressive capacity expansion, is crucial to set the table for margin sustainability in the years ahead as oil price rises and labor unions demand better working rules after years of wage austerity and massive layoffs.

A three-year long slump in oil price has resulted in a hugely positive financial impact on the airline industry’s costs, but airlines must consider the importance of capacity discipline so profits can outlast the fuel cycle. After growing 2.5 times faster than U.S. GDP in 2016, capacity is expected to return to a healthier level of 1.2 times the country’s economic output in 2018.

“I don’t view fuel in the USD 70 range as a big headwind,” says Delta chief executive Ed Bastian during the call on 12 April. “It creates a lot more discipline about the business.”

Competitive cost structure is critical to long-term sustainability. The extent to which rising fuel cost affects profitability in the airline industry depends on the ability to push up unit revenue and, hopefully, margins.

The airline industry is notoriously known for its boom and bust cycles, and unforgiving to airlines that are unable to adapt in time. The fluctuations in the market place put the carriers under severe pressure to sustain profitability and fleet optimization is critical in the vicissitudes of business cycles.

In a high-volume, low-margin environment, it is obvious that a competitive cost structure remains strategically important for business sustainability, but greater control in matching aircraft capacity to market demand results in resilient profit growth with a greater percentage of higher-fare passengers, increasing both yields and load factors.

The single-aisle sector will undergo a metamorphosis, or an evolution, once it proves equally inefficient to be deploying larger single-aisle aircraft like the A321 or larger 737s with more seats than can be profitably filled. Lest we forget, even from an operational point of view, the number of airports these aircraft can serve today is finite.

The “one size fits all” approach is clearly ageing. The airline industry is gradually evolving away from this traditional mindset in favor of the business sustainability. Within the structurally changing environment multi-class services and multiple types of aircraft to serve different missions are key facilitators to go beyond the minimum operational and financial performance required.

The bottom line is that this will be another great year for the industry, but the peak of this particular cycle is behind us. 2018 is expected to be the tenth year in a row of aggregate profitability for U.S. airlines, but the industry is facing a soft landing since 2015.

That is why it is my firm belief that the key to sustainability for an airline will be less about adapting its network to its capacity, and more capacity to its network. Some of the world’s most profitable airlines today operate numerous fleets and sub-fleets, tailored to various missions. A synonym for complexity is sophistication, and a more diverse fleet if well-managed can be a profitable one.

Written by: Victor Vieira